A Family’s Resilience

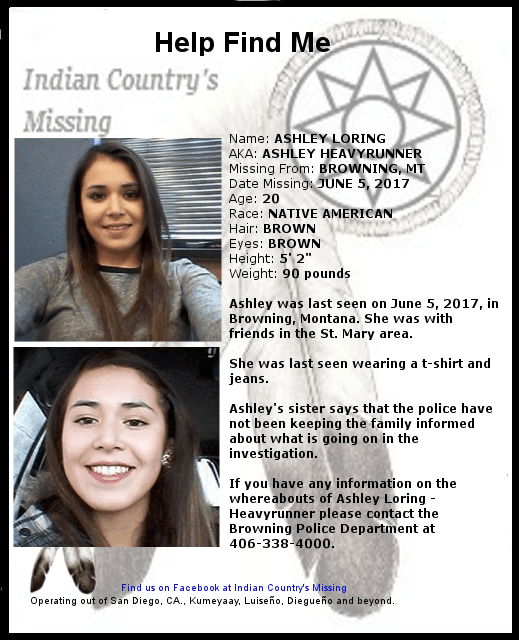

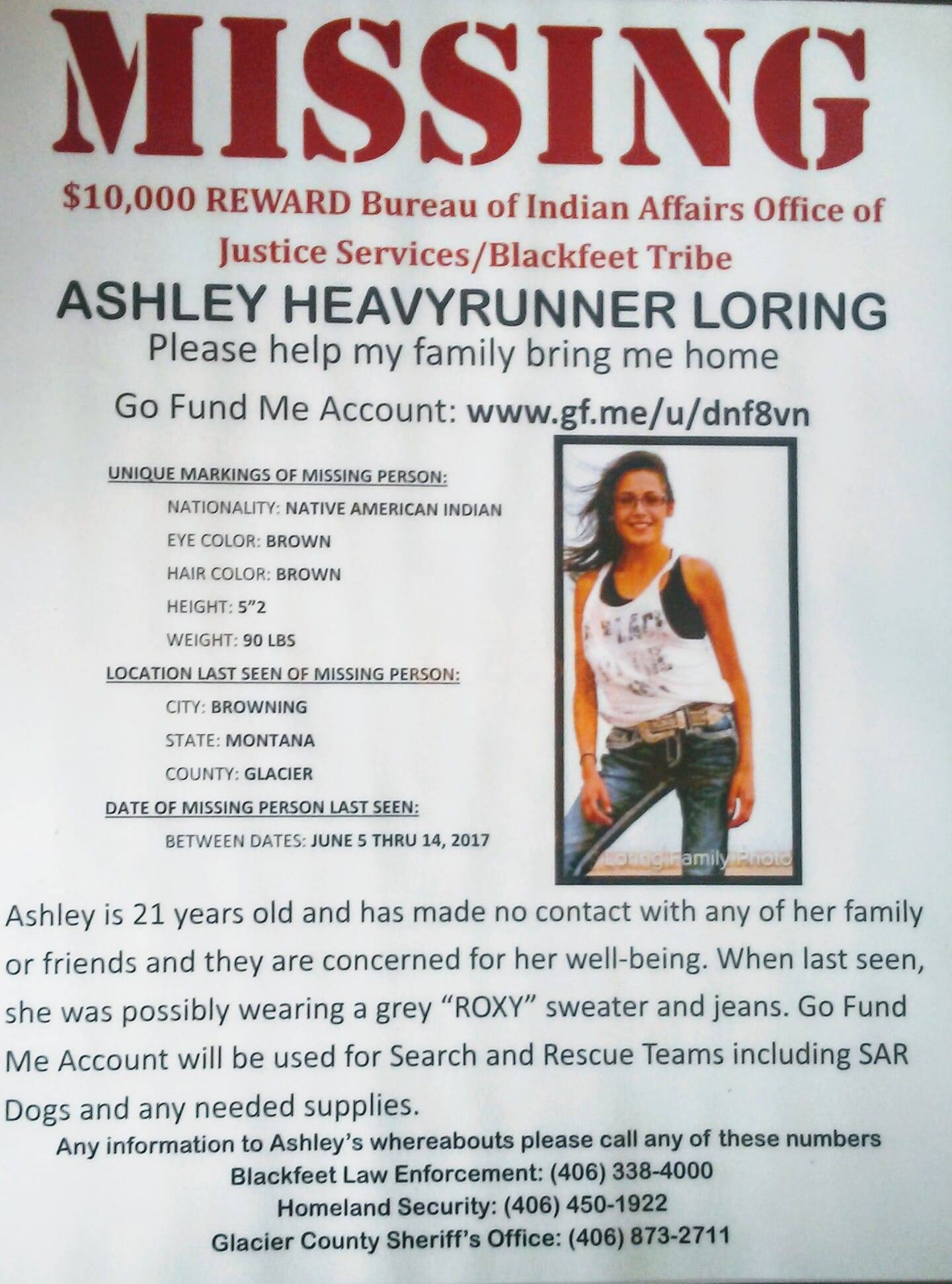

When law enforcement fails, families of missing women step up, as is the case with Ashley Heavy Runner Loring, a 21-year-old Browning woman who has been missing since June 2017

By Justin Franz

BROWNING — Ashley Heavy Runner Loring is out there somewhere.

Since June 2017, Ashley’s family has been combing the Blackfeet Indian Reservation looking for any sign of the missing 21-year-old woman from Browning. Spearheading that search effort is the missing woman’s 24-year-old sister, Kimberly Heavy Runner Loring.

When someone goes missing, it’s normal to contact the police. But when law enforcement comes up empty-handed — as is often the result in the many missing person cases across Indian Country — it is frequently up to the family and community to carry on the search.

“If I was the one in Ashley’s place, I know she wouldn’t stop looking for me,” Kimberly Loring said.

Kimberly and Ashley were always close growing up. The sisters were raised on a ranch near Heart Butte, where Ashley learned to love riding horses. In high school, Ashley was active in sports, including volleyball and cross-country. She graduated high school in 2015 and attended Blackfeet Community College. She was exploring getting into forestry and planning to transfer in the fall of 2017 to the University of Montana in Missoula, where she would live with her older sister.

In spring 2017, Kimberly, who was in Morocco visiting her fiancé’s family, hatched a plan with Ashley: When she came back in June, the two would spend a few months working and saving money before heading to Missoula.

“She said she just couldn’t wait for me to get home,” Kimberly said.

PODCAST: Hear Kimberly Loring in her own words this week on Inside the Beacon. To hear more podcasts like this one, and support independent, local journalism, join the Beacon Editor's Club.

Late on June 8, 2017, Kimberly returned home to Browning. One of the first things she did was call her sister, but she couldn’t get through. Initially, she didn’t think much of it, and rested for a day or two following the long trip from Africa. Kimberly talked to mutual friends who said that Ashley had been off with friends, and she attributed the lack of communication to her younger sister possibly losing her phone, something she frequently did.

But Kimberly started to panic when she hadn’t heard from her sister for nearly a week. On June 14, Kimberly and Ashley’s father was sent to the hospital in Great Falls for a liver condition. Kimberly frantically tried to call her sister, but she still couldn’t reach her. She went to social media to see if anyone had seen her little sister in recent days.

That’s when the stories started to roll in.

According to multiple friends, Ashley had last been seen at a party in Browning on the night of June 5, a fact confirmed by a video on Facebook. Other friends, people who had little to no contact with Ashley in recent years, started to come forward saying that Ashley had messaged them on Facebook out of the blue for a ride home on June 7. According to Kimberly, at least one person responded and said they couldn’t leave work yet. When they inquired further, Ashley went silent.

As Kimberly pushed for more information, some of the people she spoke with got defensive. Others said Ashley had been “hurt” and that someone had taken her to the mountains. But there was no way to decipher what was the truth and what was fiction. Kimberly and her family went the police.

But Kimberly said local law enforcement on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation didn’t seem overly concerned about the Ashley’s disappearance.

“They kept saying, ‘Ashley is of age and she could leave when she wanted to,’” Kimberly recalled.

So Kimberly did what any sister would do: she started looking for Ashley herself. Since June 2017, Kimberly has organized approximately 100 searches for her sister. She has talked to dozens of people, and whenever a new piece of evidence comes up — like when Ashley’s gray sweatshirt turned up at the dump in Babb — they head out to search again.

Kimberly said not everyone has been helpful and some people have even threatened her, saying that she would “end up like” her sister if she continues to ask too many questions. But Kimberly remains undeterred.

Among those who have helped in the search is Matthew Lone Bear from North Dakota. Lone Bear’s sister Olivia Lone Bear, 32, went missing in October 2017 and her body was discovered in a lake 10 months later. Lone Bear said, like the case in Browning, local law enforcement was of little help, so he organized his own searches.

Lone Bear was living in Bismarck when his sister went missing but uprooted his life to help lead the search in New Town, about two-and-a-half hours away. During the search for Olivia, Lone Bear’s family received help from another family who lost a daughter. Lone Bear said it’s not uncommon for Indigenous families to help one another when someone goes missing, which is why he’s made three trips to Montana this fall to help in the search for Ashley.

“I was in the same exact position as Kimberly,” he said. “I understand how hard it can be to organize these searches and talk to the media. It can be extremely taxing on one person.”

Kimberly said the last year and a half has been hard, but someone has to carry on the search for her sister.

“The local officers never took this seriously, and maybe if they had taken my sister’s case more seriously, maybe we would have found her by now,” Kimberly said.

Earlier this year, the Federal Bureau of Investigation took over Ashley’s case. Federal law enforcement officials declined to comment on the case when reached by the Beacon.

Kimberly said she would continue to search for her little sister, no matter how long it takes. She said while it’s unlikely Ashley’s story will have a happy ending, she still holds out hope for a positive outcome. More than anything, Kimberly just wants to find her sister so that her family has closure.

“I just don’t want her to be alone in the mountains anymore,” she said. “We just want to bring her home.”

84.3%

of Indigenous women experience violence in their lifetime

56%

of Indigenous women experience sexual violence

“The local officers never took this seriously, and maybe if they had taken my sister’s case more seriously, maybe we would have found her by now.” – Kimberly Heavy Runner Loring

730,000

American Indian and Alaska Native women have experience violence in the last year

25,000-30,000

Native women are estimated to be missing or murdered since 1900