A Community Searching

Family, neighbors and strangers unite online and on the ground to search for Jermain Charlo, as an expansive multi-agency law enforcement investigation works day and night to solve the case

By Myers Reece

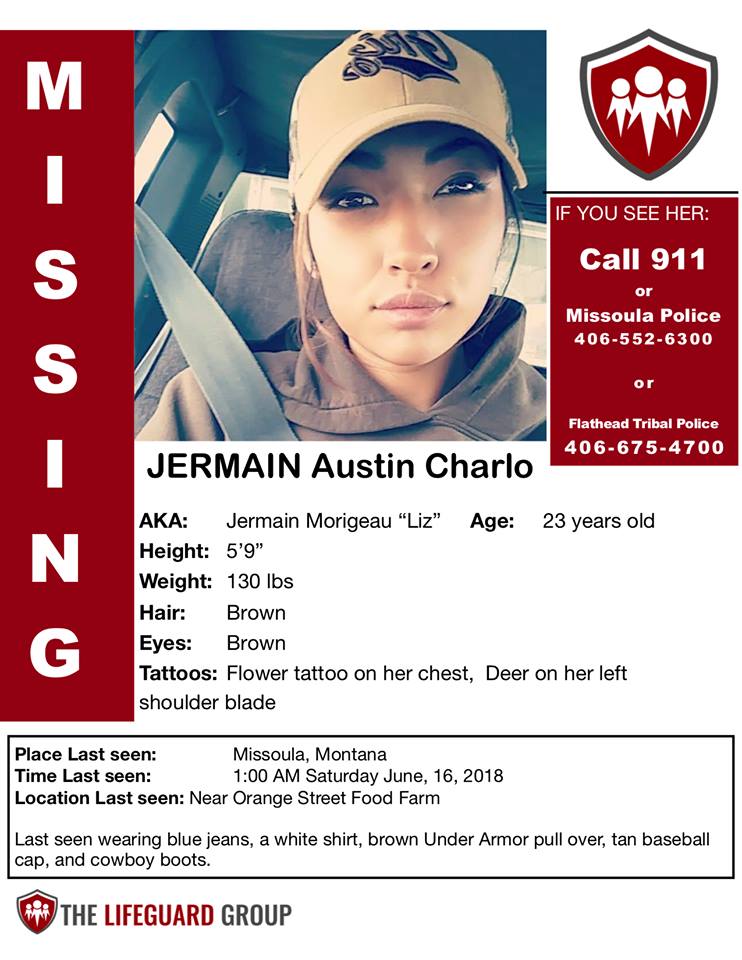

Jermain Charlo, a 23-year-old woman from Dixon on the Flathead Indian Reservation, vanished in Missoula after getting dropped off by an acquaintance between midnight and 1 a.m. on June 16.

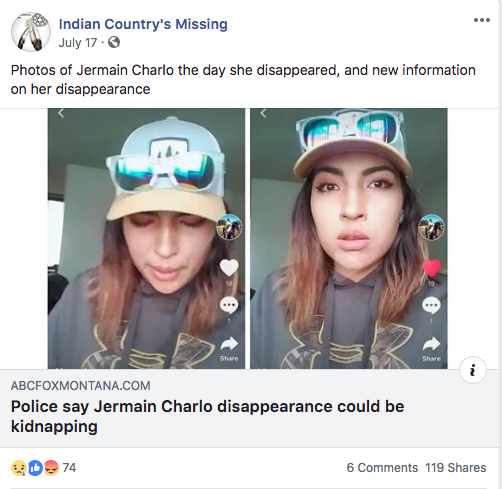

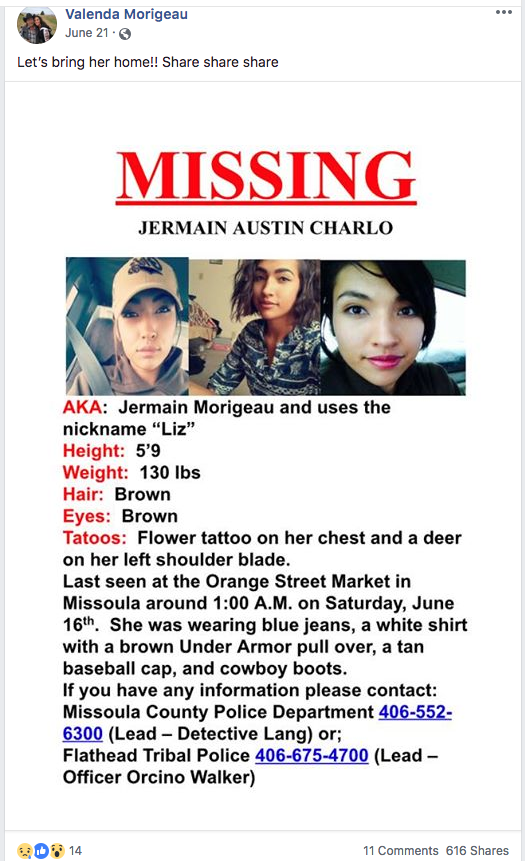

Within a week, two separate Facebook accounts — one called Indian Country’s Missing and the other Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women USA — each posted about Charlo’s disappearance, garnering more than 1,000 combined shares.

The accounts would continue posting about Charlo in the coming months, and still are, alongside others such as Save Our Sisters, a Facebook page run by Marita GrowingThunder, an advocate from the Flathead Reservation who is now a sophomore at the University of Montana.

More recently, an Oct. 1 post about Charlo by yet another similar but separate Facebook account was shared more than 4,500 times with 270 comments. There is still no trace of Charlo.

The hundreds of comments on the various pages express concern for Charlo’s safety, offer a mixture of prayers and determination to find answers, and display a general camaraderie that reflects a sprawling community of people, often strangers, from all corners of the U.S. united by a common cause: awareness and justice for missing Indigenous people, especially women and girls.

Charlo’s case has received media attention, as well as an exhaustively thorough, ongoing investigation by multiple law enforcement agencies. But many other missing Indigenous women fly much farther under the radar, failing to make headlines or launch investigations that are sufficient in the eyes of families and advocates.

That’s where these online forums step up to spread the word and fill the void, as best as possible, much like the families, friends and neighbors who mobilize back home where the missing are missed most dearly: communities coming together on the ground, face to face, and on the web, Facebook to Facebook.

GrowingThunder says that communal spirit has strengthened in recent years as the pervasive problem of missing and murdered Indigenous women attracts more attention, from national newspaper articles to growing awareness within communities, in part thanks to advocates like GrowingThunder and others who work tirelessly to shine a light on a tragedy that has too often festered in darkness.

More broadly, GrowingThunder sees Native Americans banding together more regularly and tightly in collective empowerment to fight for their rights.

“I think it has to do with the beginnings of self-decolonization and removing those binds,” she said. “There’s been so much pain that we’ve felt that has been hard for everybody to talk about and acknowledge, and it’s allowed a lot of toxicity to form underneath the skin of a community. Now that a lot more people are allowed to talk about it more comfortably and openly, they’re able to come together.”

In the last two months, against the backdrop of Charlo’s disappearance, a 15-year-old girl named Rayona Charlo from the Flathead Reservation went missing in October, while the remains of Darlene Billie, a 55-year-old woman from St. Ignatius who disappeared in October 2017, were found in North Dakota in September.

Native Americans, particularly women and girls, are murdered or go missing at a far higher rate than the general population in the U.S., although exact figures aren’t known, as many cases are either unreported or underreported — and critics say are too often undervalued — and there’s no government database tracking the cases. Lawmakers have called it an “epidemic.”

In 2018, there has been an influx in articles written about missing Indigenous women, including an Associated Press series that ran in newspapers across the nation, as well as original stories in publications as diverse as The Intercept, Teen Vogue, High Country News, Washington Post and other Canadian and U.S. news sources.

Yet, just because open conversation makes it harder to ignore troubling realities, that doesn’t necessarily translate to resolution, as evidenced by the persistently staggering rates of disappearances and violence haunting native communities across the country. Still, advocates and families hope more exposure of the issue and more voices brought into the discussion can provide a framework to catalyze substantive change.

It’s now been four months since Charlo, who also goes by the nickname Liz and the last name Morigeau, disappeared after reportedly being dropped off by an acquaintance near Orange Street Food Farm in Missoula after visiting three bars. Her social media has been dormant since then, a departure from her previously active online habits. She was last seen wearing a gray hoodie with a brown Under Armour logo, a light blue baseball cap with a tan bill and three trees on the front, jeans and cowboy boots.

Law enforcement has dedicated “hundreds and hundreds of hours” to the investigation, according to Guy Baker, a detective with the Missoula Police Department, which is heading up the investigation with assistance from the Missoula Sheriff’s Office, Flathead Tribal Police, Lake County Sheriff’s Office and the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Whereas reservations present law enforcement complexities with both the federal government and tribal police, which often lack resources, sharing jurisdictional responsibilities, Charlo’s disappearance happened off-reservation. And even if it had happened on the reservation, the Flathead has a jurisdictional hierarchy unique among Montana reservations, which gives more oversight to the state and Lake County.

For Baker, who is also a member of an FBI violent crime task force, Charlo’s case has been all-consuming, often taking up most of his week, even months later. Investigators have completed numerous searches including with cadaver dogs, examined cell phone records, executed search warrants, seized evidence and followed countless leads. The state crime lab is currently analyzing seized evidence.

“I believe that she’s the victim of a criminal act,” Baker said. “I don’t believe she committed suicide on June 16. There are people who need to come forward and share what they know because somebody did something to her.”

There are multiple persons of interest, and Baker said authorities are exploring three possible scenarios explaining her disappearance, including abduction as part of human trafficking. The acquaintance who said he dropped her off after the bars was the last person to see Charlo.

“Obviously the last person to see a missing person is a suspect until you rule them out,” Baker said.

Baker acknowledges that in instances elsewhere, law enforcement has been accused of failing to be thorough in investigating cases of missing Indigenous people, but points out the opposite is true with Charlo, with her case taking utmost priority.

“It doesn’t matter to me whether a person is black or white or native or poor or rich or whatever, they’re a person and I’m going to treat the case the same,” he said. “If other law enforcement agencies don’t do it that way, that’s a shame, but that’s not the case with the Missoula Police Department.”

“I feel that we need to do everything possible to find out what happened to her,” he added. “We need to find Jermain.”

Family and friends have also conducted searches, some on their own and others through The LifeGuard Group out of Missoula, a nonprofit organization composed of “experts committed to an aggressive, comprehensive approach to taking the fight to human trafficking.”

The LifeGuard Group mobilizes volunteers, alongside its staff, in search efforts for missing persons, working with the families and cooperating with law enforcement. Lowell Hochhalter, the director and CEO, said his group’s policy is that it will only involve itself at the specific invitation of the family.

Charlo’s family reached out to The LifeGuard Group, and to date the nonprofit has led roughly 15 searches, about half with volunteers and the rest with staff. One LifeGuard search in the area of the Flathead Reservation’s Gray Wolf Peak Casino in August involved more than 60 people.

“Some regulars have been on every search we’ve done, whether it’s been in the woods, on the street, down by the river, they’ve just shown up,” Hochhalter said. “It really gives you one of those warm, fuzzy feelings when you see people who have no tie to the family but they know a person’s missing and they jump to it.”

LifeGuard has also been active in the search for Ashley Heavy Runner Loring of the Blackfeet Indian Reservation, whose disappearance, Lowell said, hasn’t received the same investigative thoroughness by law enforcement as Charlo’s case. Lowell said his group follows up on every tip, including one that led LifeGuard to look into Charlo’s potential whereabouts in Seattle.

“You just hold on to hope,” Hochhalter said. “Whenever we get a lead, we don’t say it can wait. We jump on it quickly.”

“Somebody knows something in both cases,” he added. “And they’re just not brave enough to come forward and that’s the irritating thing. Somebody just needs to get brave and do the right thing.”

Valenda Morigeau, Charlo’s aunt, said family members, neighbors and friends have participated in LifeGuard’s search efforts, while relatives have conducted their own as well. Morigeau said her mother, Vicki Morigeau, and her sister, Jennifer Morigeau, Charlo’s mother, have been looking for Charlo every weekend. Morigeau said Vicki has a particularly close relationship to Charlo.

“My mom wakes up every day and walks over to (Charlo’s) house and prays every morning for answers and for her to come home,” Morigeau said.

“I don’t know how to explain it — there’s a huge empty spot in our hearts,” she added.

Morigeau said Charlo visited her house the day before her disappearance. Charlo was due to begin planting trees with the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes that following Monday, a job she has done regularly in past years, and was looking forward to her first summer of fighting wildfires, Morigeau said.

Morigeau’s mother has set up a GoFundMe website to raise money to put up a billboard for Charlo in Missoula, which is expected to happen soon. The CSKT tribal council has also donated money to the cause. Any additional dollars raised through GoFundMe will go toward a reward for information about Charlo’s disappearance.

In addition to the GoFundMe site, family and friends continue posting about Charlo online, as do advocacy groups.

“Right now we’re trying to keep the word out on Facebook and social media, just keeping people aware that she is still missing and to keep an eye out for her,” Morigeau said.

Baker, the detective, remains as committed to solving the case now as he was four months ago. Meanwhile, the family will wait, and search, and keep the faith.

“It’s devastating,” Morigeau said. “Some days you have hope, some days you don’t. But you always have to keep it in the back of your mind and you can’t give up, because wherever she is, if she’s alive, you don’t want her to give up either.”

Anyone with information related to Jermain Charlo’s disappearance is asked to call Detective Guy Baker at (406) 396-3217.

84.3%

of Indigenous women experience violence in their lifetime

56%

of Indigenous women experience sexual violence

730,000

American Indian and Alaska Native women have experience violence in the last year

“I believe that she’s the victim of a criminal act. I don’t believe she committed suicide on June 16. There are people who need to come forward and share what they know because somebody did something to her.” – Det. Guy Baker

25,000-30,000

Native women are estimated to be missing or murdered since 1900